She exchanges dialogue only with Jordan and seems to have no life of her own. She first appears in the film’s opening sequence, when she gives Jordan a blow job as he drives his Lamborghini. Naomi remains an object - and little else - throughout the film. Naomi reacts not with disgust but with bemused laughter. (Someone in the background then shouts, “I'd f- her if she was my sister,” followed by another, who says, “I’d let her give me AIDS.”) Enter an intoxicated and high Donnie (Jonah Hill), who, upon seeing her, begins masturbating openly at the party. In Mulvey’s terms, it’s a moment of “erotic contemplation”: The spectator is invited to drink her figure as she flashes a demure but dazzling smile before the camera.

When the camera catches her figure, time almost stands still. Anticipation builds as a Stratton associate alerts the men at the party to look at her. In the scene in which the blonde first meets Jordan, she wears a dramatic skintight blue minidress with a cutout revealing a good part of each breast. One-dimensional Naomi (Margot Robbie) - Jordan’s second wife and the main female character - is coded all over. Hollywood creates “magic” through a manipulation of visual pleasure, coding the erotic “into the language of the dominant patriarchal order.” This isn’t the fault of an individual director per se. Film theorist Laura Mulvey wrote about the concept in a 1975 essay, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in which she explains that Hollywood often forces the audience to see a film from a male perspective, causing women on screen to serve as simple objects of desire. Put more precisely, “The Wolf of Wall Street” is dominated by the male gaze - the gaze of Jordan, of Scorsese, of Winter and of the assumed audience. The breasts, stilettos and shimmying bottoms continue, ad nauseam with all the titillation, it starts to feel like the filmmakers are being seduced by the very Wall Street machismo they purportedly critique. Instead, Scorsese and Winter carry on in shot after shot, displaying dozens of barely clothed or naked female bodies whose not-so-private parts are meticulously waxed or shaven. Scorsese and Winter had plenty of creative freedom in their treatment of Jordan’s story all that was needed to show how marginalized women were on the Wall Street trading floors of the 1980s and 90s were a few key scenes featuring prostitutes and parades of strippers. Interchangeable Barbie-doll figures, hookers and strippers serve simply as props for the male protagonists as they carry on with their debauched antics, drawing plenty of laughs from the audience. “Wolf” fails to say anything interesting about the women who inhabit Jordan’s world. Unfortunately, by using women as little more than playthings throughout the film, the creators of “Wolf” have given in. While “Wolf” is based on a true story and real characters, there is a fine line between accurately depicting the rampant objectification of women in Jordan’s world and succumbing to it. What’s received far less attention than merited, however, is the film’s portrayal of women. The film is also a comedy - albeit a black comedy - that invites its audience to laugh and even marvel at the crass frat-boy antics on display. For one thing, the victims of Jordan’s fraud - i.e., those who spent their life savings on worthless penny stocks or lost big when Jordan manipulated stock prices - are absent from the film. While critics have largely praised the film, it’s drawn some heat for glorifying the exploitative, hedonistic lifestyle it depicts. Along the way, he and his colleagues indulge in vast amounts of sex, drugs and reckless behavior - all of which the film forcefully foregrounds.

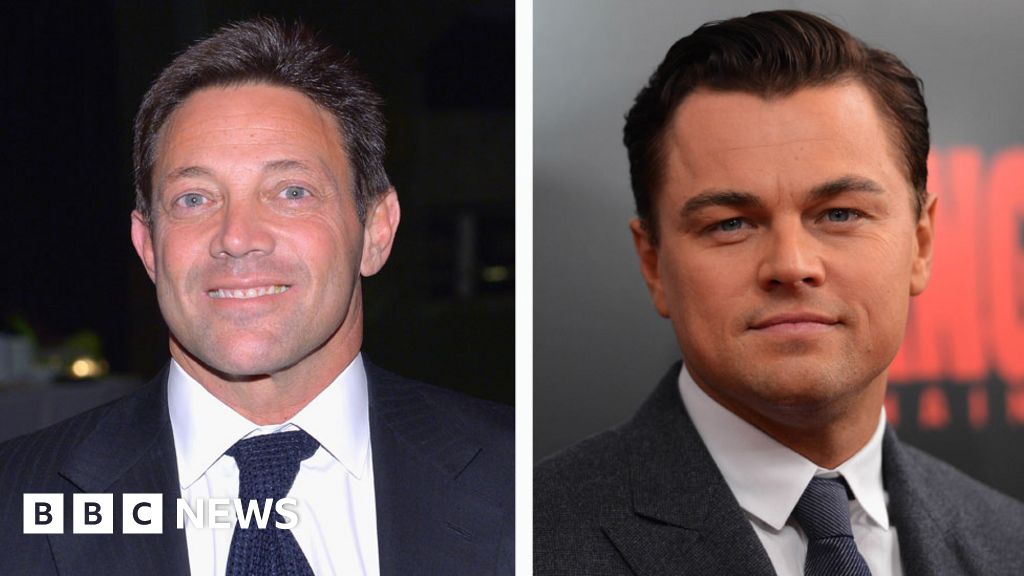

Jordan, a master salesman who develops a cultlike following, amasses a fortune by pushing questionable stocks to investors with hard-sell tactics before graduating to stock manipulation and money laundering. Told in part through voice-over narration by DiCaprio, it shows Jordan’s rise from small-time penny-stock trader on Long Island to the founder of Stratton Oakmont, one of the largest brokerage firms on Wall Street in the 1990s - all by the time he is 26 years old. Martin Scorsese’s “The Wolf of Wall Street” tracks the journey of real-life finance scam artist Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)